THE GLENGARRY CAIRN RETURNED

After slightly more than a century, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne announced late last year that, following more than “…15 years of diligent efforts,” the Akwesasne Rights and Research Office formally secured the return of Cairn (Tsikatsinakwahere) Island to “…the Akwesasne Reserve through Ministerial (Federal) Order.”

In concluding their remarks, the Council stated that, “The Island, deeply woven into the identity and traditions of the Mohawk people, will once again serve as a place of cultural and historical significance.”

The question that immediately came to my mind was: how was the island lost?

It turns out that it was expropriated against the wishes of the Band Council in 1922, during a time when the Federal Government was intent on assimilating Indigenous people through “…laws designed to further remove Traditional land.”

Professor Katie L. McCullough traces the “theft” in her insightful article about the Glengarry Cairn written in 2021.

First, a history of the Cairn before delving into the details of how the Island was “lost.”

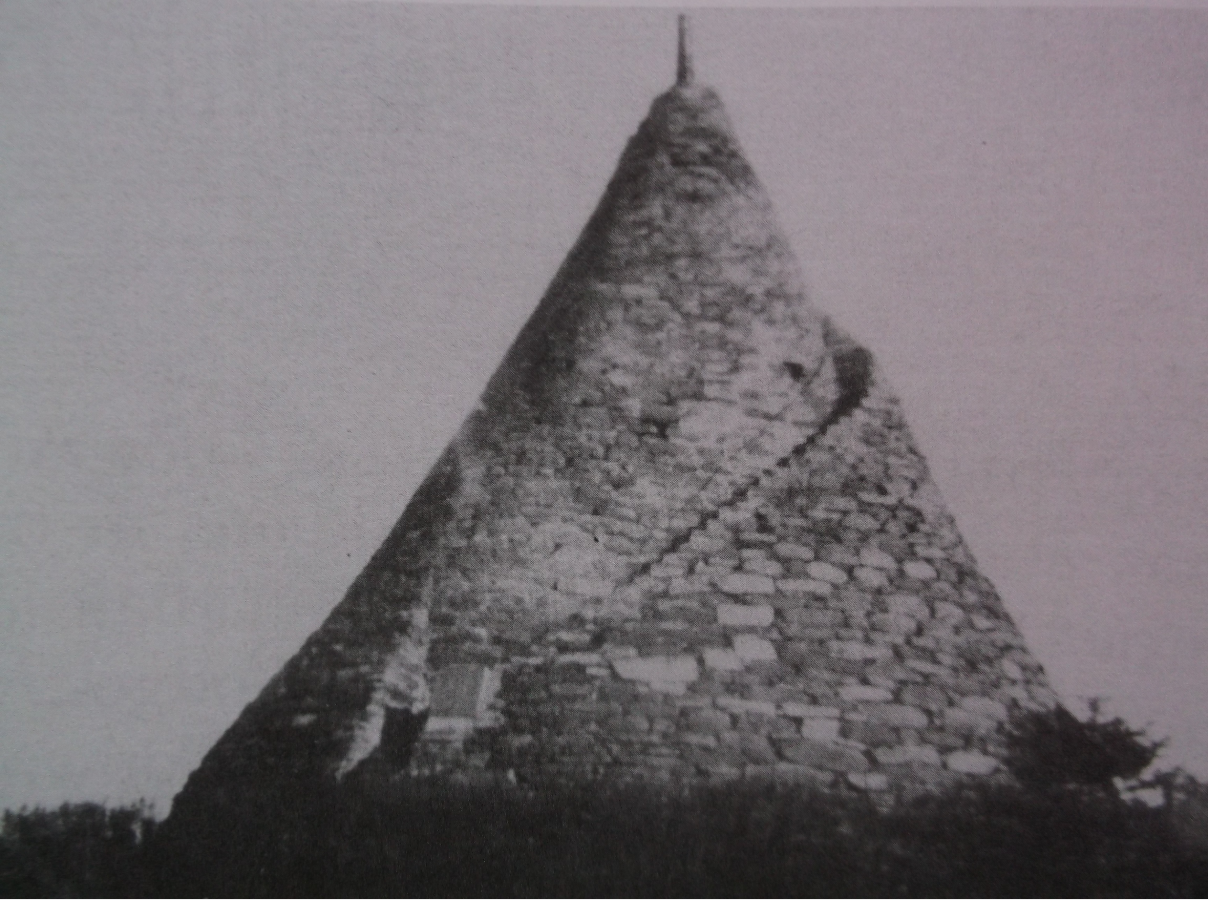

Constructed by the Glengarry Militia from 1840-42, the plaque installed on the monument by proud Glengarrians in 1905 reads:

“This cairn was erected under the supervision of Lieutenant-Colonel Lewis Carmichael of the Imperial Army, stationed in this district on particular service of the Highland Militia of Glengarry, which aided in the suppression of the Canadian Rebellion of 1837-38. To commemorate the services of that distinguished soldier Sir John Colborne…who commanded Her Majesty’s Forces in Canada at that critical period…and had particularly distinguished himself at Waterloo…was Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada from November 1828 – January 1836, Governor-General of Canada in 1839, and afterward became Field Marshal Lord Seaton G.C.B.”

Forty-five feet tall and surmounted by a Napoleonic-era cannon-turned-flagpole, the plaque tells a nice story but leaves out two important points.

First, local folklore maintains that the cairn was really a “make-work” project to keep idle militiamen, quartered in Lancaster, out of harm’s way. More importantly, they did not receive permission from the Mohawks who owned the island to occupy it!

In 1921, the cairn became a National Historic Site, and a year later, the island was expropriated against the stated wishes of the Mohawks of Akwesasne, “…until such time as satisfactory settlement of certain leases” was reached. In other words, the Band Council, “…bedeviled by unpaid rents, squatters, and shifting government policies” regarding their islands in the St. Lawrence, were not about to give up possession of the island until these matters were resolved.

Today, that would have been enough to prevent the seizure, but the Federal Government in the 1920s was bent on assimilating Indigenous peoples and passed laws making such actions “legal.”

In 1919, Parliament strengthened the Expropriation Act of 1911 by allowing such seizures if the land was required for the “purpose of a Dominion Park.” Despite the Band Council’s protests, the Government used this clause in 1922 to invoke a Governor-General Order in Council, paying $100 for the transfer of the island to create Glengarry Cairn National Historic Park.

The matter remained more or less out of sight until 1997 when workers for Parks Canada found human remains around the base of the monument, suggesting that this was an ancient burial ground. Now sensitive to Indigenous rights, Parks Canada passed the island’s stewardship over to the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne. In 2009, erosion to the island and deterioration of the cairn led to its closure to the public. In 2015, Parks Canada began working with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne for the island’s return, a feat not accomplished until late last year.

Now, I wonder when the government will pay due respect to Cornwall’s forgotten Metis cemetery?