Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity pays to greatness. – Oscar Wilde

Picasso is famously quoted as saying, “Good artists copy; great artists steal,” a statement

distinguishing between simple replication and the transformative use of existing ideas to create something new and unique. He used “steal” to mean creatively incorporating influences and making them one’s own, not simple plagiarism.

It is also true that far more people know of the Mona Lisa than have actually seen it. A photograph of a painting, for instance, can be endlessly reproduced and taken out of its traditional context, like a museum. The focus shifts from the work’s exclusive presence to its accessibility for a broader audience; books and magazines to the Internet have allowed countless artists access to works that they may never have seen, were it not for reproduction. This very access to some degree helps to elevate and popularize the original work when artists find various new ways to represent the old.

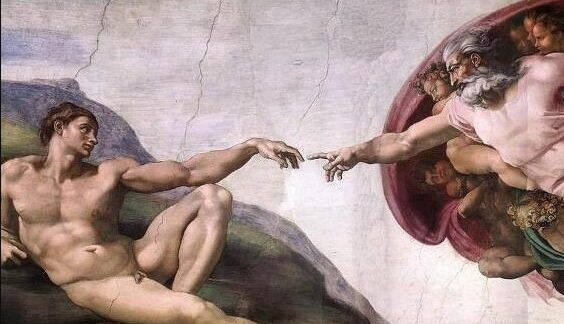

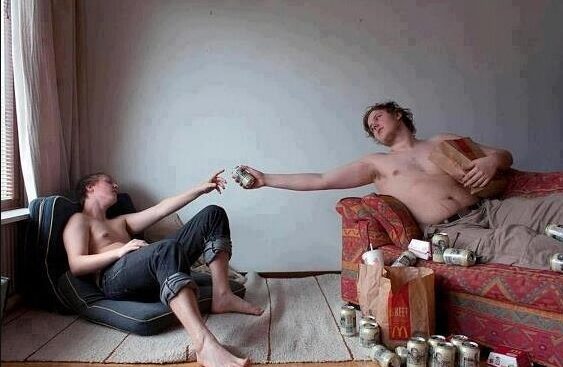

In remaking the old, contemporary artists might draw on any number of visual and metaphorical tactics that may call up the old works to those in the know. Five hundred years after Michelangelo created The Creation of Adam, 1512, an Internet blogger in 2012 responds with this satirical take that is an obvious and hysterical reference to the original work.

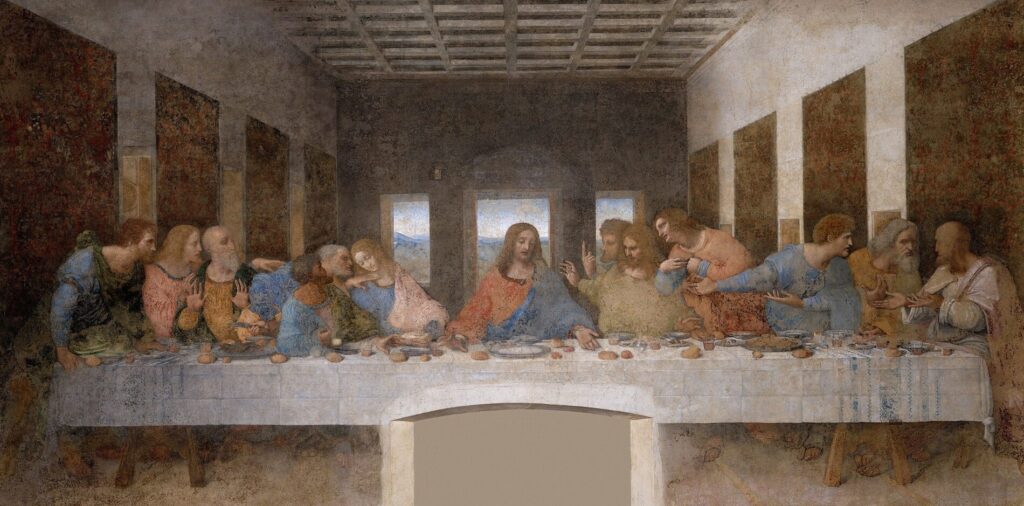

Adi Nes described his photograph The Last Supper, 1999 as a reflection on the uncertainty and potential for death in Israeli society, where all individuals could be seen as experiencing a “last supper” due to the constant threat of conflict, suicide bombings, and military service. He intended the piece to challenge traditional notions of strength by depicting soldiers in a vulnerable, intimate setting, drawing parallels between their lives and Jesus crucifixion to explore themes of mortality, duty, and identity, particularly his own experience as a gay man feeling like a stranger in mainstream Israeli culture.

Consider the original work by Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495-98, it is a work of renown that set a precedent that would be copied for generations. The irony doesn’t escape me that both works are representations of Jewish men.

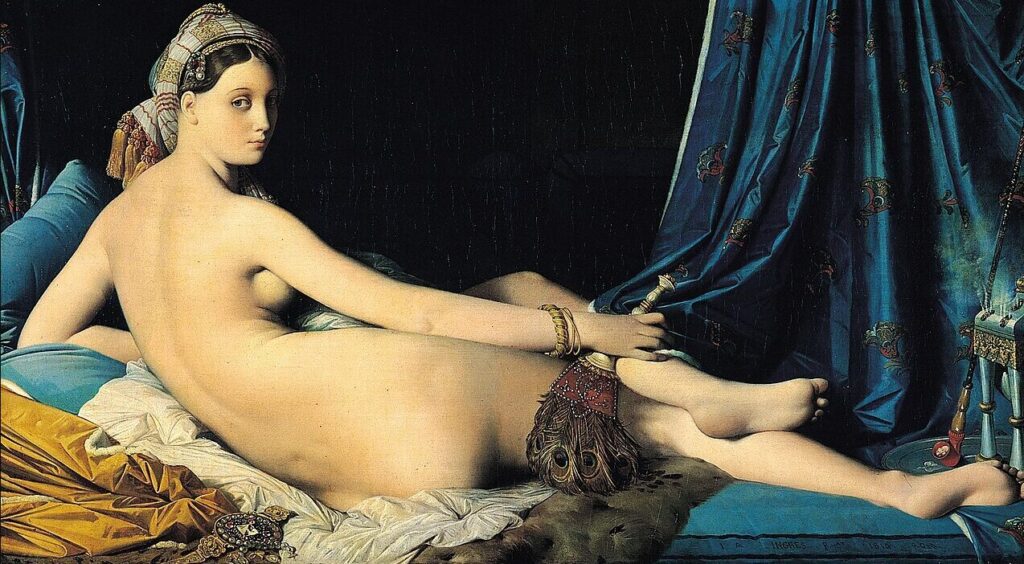

In a backlit photograph contemporary artist Rebecca Belmore’s work Fringe, 2008, calls up another long standing artistic tradition of depicting the female body; her study of the female form clashes and critiques the odalisque (a harem concubine). The subject was popular with male artists like, Renoir, and Matisse, and the genre reflects Western fascination with the East, often portraying nude or partially nude figures in an Orientalist context. Here we see how Belmore either consciously or subconsciously subverts the classical – La Grande Odalisque,1814 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Belmore states “as an Indigenous woman, my female body speaks for itself. Some people interpret the image of this reclining figure as a cadaver. However, to me it is a wound that is on the mend. It wasn’t self-inflicted, but nonetheless, it is bearable. She can sustain it. So it is a

very simple scenario: she will get up and go on, but she will carry that mark with her. She will turn her back on the atrocities inflicted upon her body and find resilience in the future. The Indigenous female body is the politicized body, the historical body. It’s the body that doesn’t disappear.”