Special Contribution to the Seeker

Eastern Ontario’s citizen-soldier settlers, as former members of the British Army where they were authorized to receive six pints of small beer (low alcohol) per day “for their health and convenience,” had an enduring taste for alcohol. And across Upper Canada, wherever British forces were settled or garrisoned, a brewery and/or distillery usually followed.

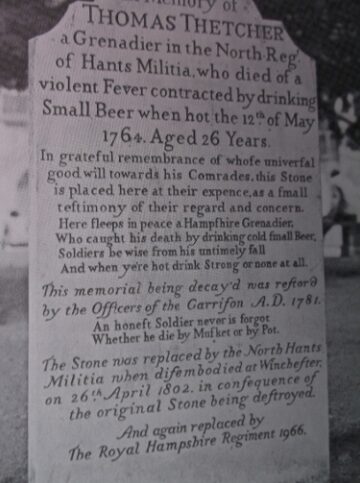

(Photo 1 – caption:) This refurbished 1764 tombstone to British Grenadier Thomas Thetcher proclaims: “An honest Soldier never is forgot Whether he die by Musket or by Pot.”

In the 18th century, the word “pot” meant a beer tankard, not something you smoked!

Cornwall was no exception.

The story of Cornwall’s distillery begins when Rebels confiscated Royalist merchant Joel Stone’s property in the Connecticut Colony in 1776. In response, he joined the Loyalists and eventually reached the rank of Captain.

In need of rebuilding his fortunes, Stone left his wife, Leah, and family behind for England to petition the government for reparations to cover his wartime losses and secure his wife’s inheritance from her deceased uncle. Arriving in London in December 1783, it took 2½ years to settle the will.

Stone now planned to return to North America and purchased “three stills to make whiskey” and gin to meet the Loyalists’ love of ardent spirits and turn grain into cash through distilling.

With this plan in mind, Stone sailed with his equipment to Quebec, where he was reunited with his less-than-content wife. Intent on opening his distillery in a growing community, Stone, as a Loyalist officer, petitioned for a grant of land in New Johnstown (Cornwall) in February 1787, only to learn that all available lots were taken.

Undaunted, Stone purchased some 40 acres of land and arrived here with his family and three full bateaux — no doubt laden with his distillery hardware — in March 1787.

Shortly after his arrival, Stone built the distillery, possibly making it Cornwall’s first industry and conceivably Upper Canada’s first. As his equipment included a malt kiln, it is clear that Stone intended to produce a rough colonial version of Scotch. Unfortunately for Stone, 1788 saw agricultural shortages caused by a drought the previous year, a situation exacerbated by the Crown ending subsidies to the Loyalist settlers.

Forced to wind up his Cornwall estate due to his divorce from Leah, the distillery grew to include a brewery, while Stone moved to Gananoque. If the brewery was operational between 1788 and 1792, it also may be Upper Canada’s first brewery, predating Finkle’s Brewery in Bath, founded circa 1793. Sadly, as explained below, without further details confirming these dates, I am going to have to settle with 1795.

(Photo 2 – caption) Finkle’s log brewery and tavern near Bath was believed to be Upper Canada’s first brewery; however, recent research suggests that Joel Stone’s Cornwall brewery may be the province’s first. Stone’s brewery would have been a simple log or frame structure similar to the one shown here.

Stone’s Cornwall works were acquired by Richard and Marianne Warsse. Warsse’s distillery remained in business until 1795, when a notice in the November 23 edition of the Quebec Gazette informed creditors that the distillery was in default.

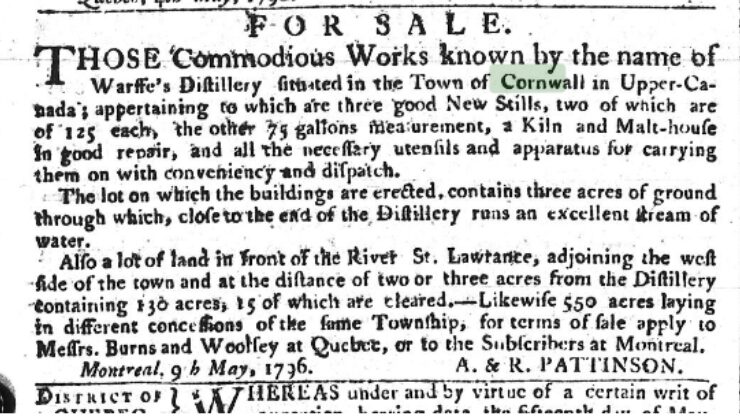

In 1796, the Warsses placed a for-sale ad in the Quebec Gazette describing the distillery. This rare depiction shows that the facility was outfitted with “three good New Stills… Kiln and Malt-house,” used in producing both beer and Scotch, and situated next to an “excellent stream of water” (Fly Creek), a basic ingredient in both beverages. These facts make it almost certain that the Warsses were brewers and distillers.

(Photo 3 – caption) May 9, 1796, Sale Notice, placed in the Quebec Gazette. The “f” letter in the Warsse’s name is known as the long “f” and fell out of usage around 1800.

From the available records, I believe that the factory was located on the southeast corner of Cumberland and 4th St. W., diagonally across from Rurban Brewery today.

The last mention of Stone/Warsse’s operation appears in a letter written in April 1797 by John Macdonell of Scotus to his son, informing him that a “Mr. Gershon(m) Levi (Levy) from Montreal makes beer and distills whiskey at the place once Stone’s.”

If you have worked up a thirst by following me this far, you probably wonder what the beer may have tasted like. You are in luck, as I happened to have brewed a keg of beer from a period recipe to sample during my Master’s presentation at the University of Toronto.

First, it did not taste like any India Pale Ales on the market today, as the style wasn’t developed until the early 19th century. It could have been a stout similar to Guinness but was much more likely to have been an unfiltered, malty, gently hopped, full-flavoured brown ale — or, if you like, a mug of “liquid bread.” While North America’s craft brewers are making almost everything that was ever called beer, with the notable exception of Wellington “Brown Ale,” there is nothing even like it on the market today. And even then, to fully appreciate this traditional tipple, it is best to enjoy an unrefrigerated, unfiltered, cask-conditioned sleeve of this elixir — if you can find it!

Cheers!

P.S. One of the highlights of my beer-tasting career was arriving home one Friday afternoon to discover a complimentary mini-cask of brown ale in the kitchen that had been Purolated to me by the good folks at Wellington County.