On the Road Again – Public Art

Public art is more than art outside:

● It’s accessible to everyone

● It’s enriches and enlivens public spaces

● It can be an economic driver for tourism

● It can be commemorative and/or celebratory

● It inspires learning, dialogue, and civic engagement

● It can be digital, sculptural, a mural, a performance–it can be interactive

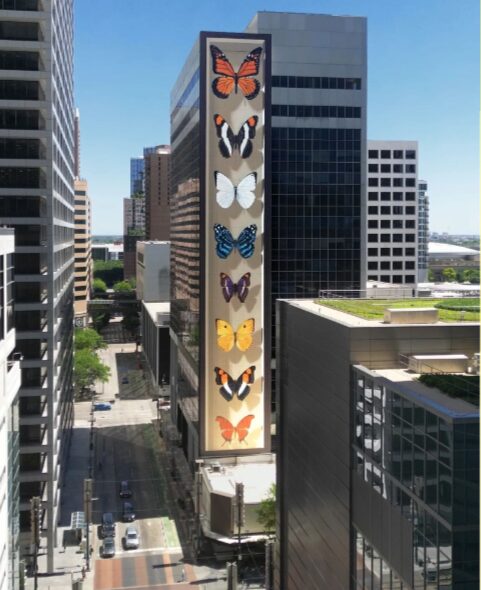

Trompe-l’œil, French for ‘deceive the eye’ is the highly realistic optical illusion of three- dimensional space and objects on a two-dimensional surface. It is this Renaissance style that is used by the French artist Youri Cansell, a.k.a. Mantra.

Mantra’s highly realistic artwork can be seen in countries all over the globe; his towering 233- foot/71 meter tall mural, a narrow composition painted freehand in downtown Houston, draws on a fascination with nature and its preservation. Mantra creates monumental specimen cases, filled with a wide variety of butterflies. He transforms brick facades and concrete walls into

massive studies of local butterfly specimens.

Mantra, The Houston Collection, 2024

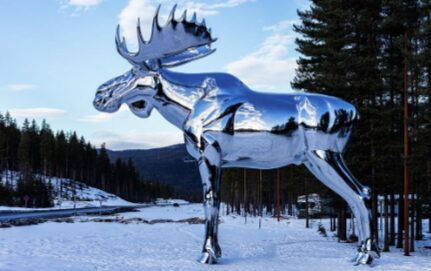

Up until 2015, the Moose Jaw sculpture “Mac the Moose” had no rivals to the title of world’s tallest moose, standing 9.8 meters (32.15 feet) tall. But then Storelgen (in Stor-Elvdal, Norway)

unveiled its 10.1 meter (33.1 feet) tall moose, dressed in eye-catching shimmering silver appeared, attracting the attention of passing motorists, many of whom stopped at the rest area for a closer look.

Mac the Moose is a steel and concrete sculpture in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, on the grounds of Moose Jaw’s visitors’ centre. In January 2019, two Canadian comedians urged Moose Jaw residents to add 31 cm (12 in) to Mac’s height (likely by extending his antlers or giving him a helmet), so that the moose statue would once again win the title of the world’s largest moose.

In October 2019, Mac regained the title of the world’s tallest moose when a new set of antlers was installed, raising its height to 10.36 metres (34.0 ft), making it taller than the Norwegian sculpture.

Don Fould’s, Mac the Moose, 1984 Linda Bakke, Storelgen or “The Big Elk” 2015

Lionel Peyachew’s life-sized bronze sculpture titled “Wicanhi Duta Win (Red Star Woman)” sits outside the headquarters of the Saskatoon Police Services building. It is a powerful symbol of remembrance for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. It depicts a woman dancing on a cloud, her shawl transforming into eagle’s wings as it trails behind her. The piece

was modelled on Amber Redman, a young woman from Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation who disappeared in 2005 and was later found to have been murdered.

At an emotional unveiling ceremony in 2017, the artist Peyachew addressed the crowd about the importance of working toward effective prevention and meaningful justice for the missing and murdered, saying, “Never give up.” The work reflects transformation, hope, ceremony and memory.

Lionel Peyachew, Wicanhi Duta Win (Red Star Woman), 2017

The Spinning Chandelier designed by the late BC born artist Rodney Graham sits under the Granville Street Bridge at the entrance to Downtown Vancouver, Granville Island, and False

Creek. A site that was once an industrial and commercial waterfront now houses million dollar condominiums, weighing over 7,500 lbs it is constructed of stainless steel, LED lamps, and over 600 polyurethane faux crystals.

The chandelier lowers twice a day at a fixed time, releasing and spinning rapidly before

ascending back to its lofty starting point. At night it lights up, cascading reflections on a very dark part of a now gentrified neighborhood.

Rodney Graham, The Spinning Chandelier, 2020

When the Rubber Meets the Road, 2018 by PEI artist Gerald Beaulieu are two crows made entirely from recycled tires, each measuring 16 feet long, it’s placed along the multi-use pathway on LeBreton Flats in Ottawa. According to the National Capital Commission “the harm caused by our commuter culture as well as the crow’s role as a scavenger of urban waste “ – LeBreton Flats used to be the site of a landfill, making the recycled content especially significant.