It was a Macabre Ending: A ten day investigation, headed by the chief of police, concluded that Cornwall Jail Governor Ralph A. Cook, for some unknown reason, arranged his own May 7/8, 1938 alleged suicide to appear as a murder. The chief of police stated:

“Had it not been for the existence of strong motives for suicide, we would undoubtedly have proceeded in our investigation with the belief that this was a case of murder.”

Although kept secret by authorities and Cook himself, even from Cook’s own family, on April 25th the 57 year old Cook had been suspended for the duration of a provincial inquiry. Two days later, he made his will. As far as the family and others knew, Cook was on vacation for most of the ten day period leading up to his death. During that time, he spent much of his time at his Farran’s Point garage and had been to his farm in Osnabruck Township. On Friday May 6th, he had been notified that his services were no longer required; Cook’s family were still unaware until after his death.

That Day

It came to light that Cook had purchased a file at Bowra Hardware before leaving for Farran’s Point at about 10 a.m. that morning. That night in the bar at the New Windsor Hotel near the jail, Cook was reported to have said to a friend: “This one is on me; you may not see me again.” Returning to his family home around 10 p.m., Cook was cheerfully and normally conversing with family prior to listening to the 11 p.m. radio news as usual. He announced that he was heading outside to move his car from the driveway into the garage; apparently he had planned to visit a man in the east of town that evening on a business matter, but didn’t get to it. Thus the reason for the car not having been parked in the garage earlier. He never returned to the house.

The Scene

At 2 a.m., concerned over her father’s prolonged absence, Ralph’s daughter Grace entered the jailors’ garage, but did not see her father there. Further alarmed, she went to her brother Dalton’s nearby commercial garage (where he also slept) to recruit his help. Together they returned and observed their father’s partially obscured dead body between his vehicle and a pile of planks against the west wall. Cook was on his back with a rifle partly under his feet and one arm on the car running board, with his old fur coat under his head. The coat had been stored hanging in the garage for some time. Dalton summoned Jail Turnkey James Cowhey to call for the police. At the time, Cowhey’s family had been living in the house attached to the Jail, no more than 20 feet from the jailors’ garage. That house was generally used to accommodate the Governor’s family. Police arrived around 3 a.m. The Coroner arrived and was of the opinion that Cook had been dead for some time, possibly since before midnight.

In spite of two rifle shots and the lateness/quiet of the hour, no one in the vicinity, neither the two resident jail turnkeys, nor Cook’s family, nor the 31 inmates, nor neighbours, admit to having heard any shots fired.

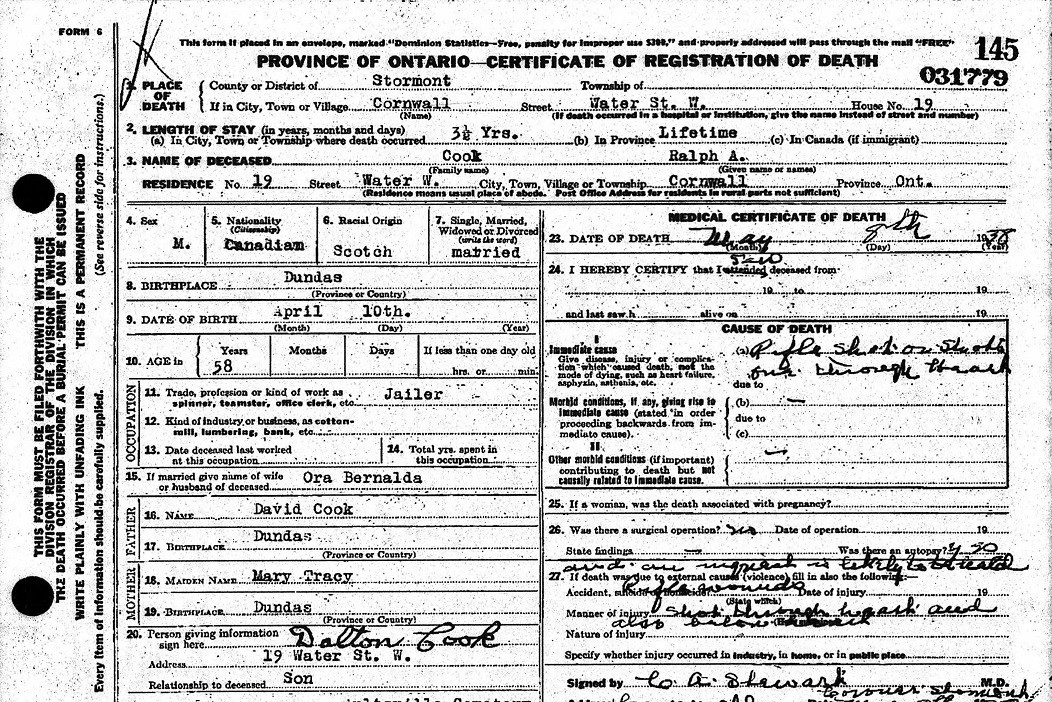

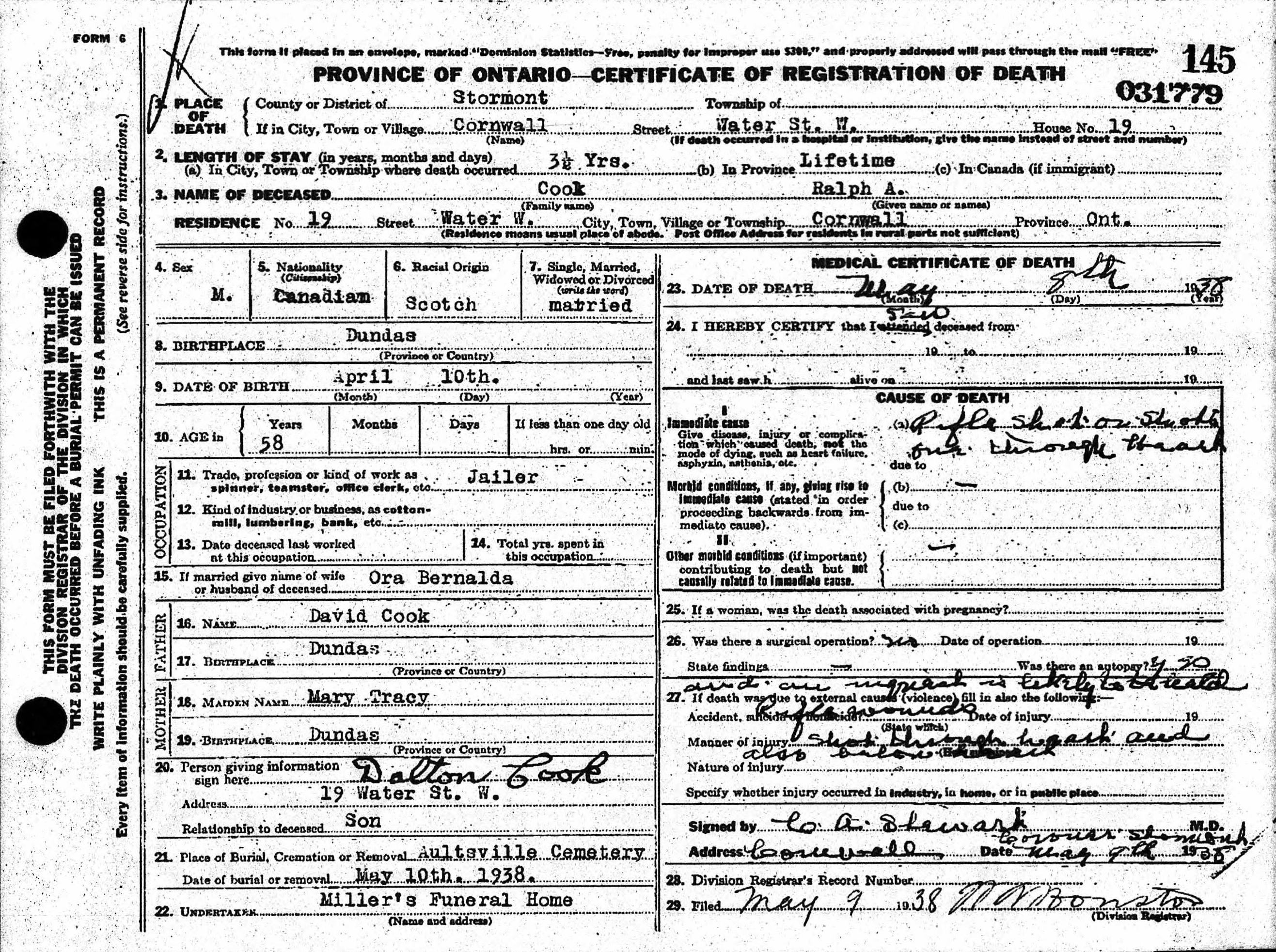

His Wounds

Cook was shot with two long-rifle .22 calibre bullets to the left chest, one piercing his heart, the other within 1-2 inches of the heart. The brand new rifle was a single-shot fire arm of the type commonly used for small game and would have required strength to re-load and shoot a second time.

The Weapon

Identifying marks had been freshly and cleanly filed off the breech and barrel. Metallic filings were found in Cook’s pant cuffs. One exploded cartridge remained in the breech; the other was found on the garage floor. 8-10 feet from Cook’s body were two unexploded cartridges wrapped in a bit of newspaper. Cook’s vest contained traces of unburned powder or nitrates and discolouration, which were suggestive of the rifle having been pressed against the fabric when the shots were fired.

A single useless partial print was found on the gun. The Chief of Police acknowledged that:

“If Mr. Cook took his own life, it is virtually certain that he could not have wiped off the rifle after firing the second shot.”

His family insisted that Cook owned no firearms, nor knew how to use them. None of the local merchants between Cornwall and Chesterville reported selling such a weapon in the month or so prior.

Acid etch revealed the rifle to be of the Eaton’s ‘Eatonia’ brand and bore no serial number. Etonias were re-labelled Cooey Ace #3s.

On May 3rd, a man giving the name of R.A. Cooke of Manistee, Michigan, purchased such a gun at Eaton’s in Toronto. Cook was believed to have been in Toronto at the time. The clerk remembered the man and provided his physical description, which did not entirely match that of the deceased governor. The man who purchased the rifle in Toronto was described as being 5’8″ in height; Ralph was 6’2″. Incidentally, Ralph’s son, Garnet Cook, was living in Toronto at the time and happened to be 5’8″ tall.

Money – $170 of $175 Missing then Found?

When Cook’s body was found, his wallet was missing and his hip wallet pocket was turned inside-out; the family estimated that the wallet should have contained about $200. At about 10 a.m. the next day, Turnkey Maloney discovered the wallet in the garden about 100 feet behind the garage where his body was discovered. It contained two $1 bills.

A few days prior to his death, Cook cashed a cheque for $175 at a local bank and received payment in 15 $10 bills and five $5 bills. 15 $10 bills and four $5 bills were found in an old purse in an upstairs dresser. His family could not explain it, but did not believe it was the same money missing from Cook’s wallet. They were certain that Cook had not gone upstairs after entering the house on the Saturday night prior to his death.

Did Ralph Cook somehow manage to kill himself or did he perhaps believe that someone else might be planning to do him in? Will we ever know?

Originally buried at St. Paul’s Church Cemetery in Aultsville, Ralph Cook was re-buried at St. Lawrence Valley Union Cemetery when his original gravesite was submerged by the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958. His widow was buried with him following her death in 1961. Photo: Jeff Ebner.

Thank you to John Bulloch for the photos of Ralph Cook, his farm and Garnet Cook. New Windsor Hotel photo courtesy of S.D. & G. Historical Society. Much of this historic look back in time is based on information reported in the May 9-16, 1938 Standard-Freeholder news articles pertaining to the case.