The weaponization of import tariffs by the American Republic party, to pressure Canadians into joining the United States, is an old story. It is a tactic that failed in 1890, when President McKinley introduced tariffs, and is failing now.

Instead of strengthening the Republican’s hold on Congress, they were severely trounced in the 1890 mid-term elections by the Democrats, after they were introduced.

Rather than buckle to the inducement to join the republic to the south, the veiled threat led to a renewed sense of Canadian nationalism. (Does this sound eerily familiar?) And many Canadian entrepreneurs strengthened or founded their own production facilities, to increase their share of both national and overseas markets, while the Federal government enacted retaliatory tariffs.

Internationally, the import tariffs imposed by America’s “Napoleon of Protectionism,” President William McKinley, depressed international markets, particularly in Latin America, and led to countries worldwide imposing matching import duties.

In Chesterville, farmers’ reacted by forming their own facility to produce condensed milk. Historian O.D. Casselman, and condensery owner wrote, that the village’s first refrigeration plant, necessary for the production of condensed milk, started as a farmers’ cooperative, as a direct result of the tariffs, just north of the railway tracks, between 1893 and 1900, on land that would one-day be the home of Nestle Canada.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

The story of Chesterville’s first condensery is murky at best, particularly as the business appears under several names, and the topic needs more research, but the following is what I have pieced together after considerable “head” scratching!

The story jells with the incorporation of Canadian Condensery Co., Ltd., of Chesterville, in 1907, a move that paved the way for “milk to become king.”

Producing Royal Condensed Milk and Imperial Evaporated Cream, the Condensery harked back to its origins in a flyer that boasted that their products “won the highest awards at the (1893) Chicago World’s Fair.” They continued that the “brand owes its fine quality to the freshness and purity of the fresh milk or cream. It makes a perfect and naturally complete food for infants, nursing mothers, invalids and aging people, or anyone troubled with weak digestion.”

Despite these fine words, the operators according to Casselman, could not find an adequate water reservoir, and lacked the experience in “…the intricate process required to manufacture a perfect product,” and gave-up “After a few years of fruitless effort to turn out a product as good as those already on the market.”

Enter American entrepreneur Howard G. Carter, promoter of the newly formed Maple Leaf Condensed Milk Co. Ltd. Incorporated, who without a factory, asked the Dairy Section of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture to advise him on the best place to open a plant, only to be directed to locations in Southwestern Ontario. Not satisfied with the results, Carter continued his search and six months later heard that Chesterville was the ideal location. He now visited the site and despite the plant’s poor condition, saw potential, leading him to ask for tax exemptions, a railway siding and functional sewage system. With anti-American sentiment long over he now “sweetened” the deal for local politicians, by informing them that Charles Hires, of root beer fame, would be interested in acquiring a refurbished plant. The ground-work laid, Carter acquired the site from O.D. Casselman, demolished the old plant and built a new “turn-key” condensery, that he sold to Hires Condensed Milk, in 1915. All was not smooth-sailing, however, and tragedy struck when the 50,000 gallon water tank collapsed a year later killing workman George Fykes.

Despite this disaster, Plant Manager, G.F. Sayles was able to turn the operations around and advertise in the “Chesterville Record,” of September 24, 1917 that Maple Leaf Condensed Milk offered “SERVICE.”

The advertisement continued:

“It is a great satisfaction to know that you are dealing with a dependable, straight forward company, who through years of experience are able to take care of your needs adequately.”

“You can bank on the Condensery, with its progressive organization and thoroughly equipped plant, to win your approval in its service in handling your milk.”

The business continued to thrive throughout the War, with Sayles assisted by H. Hooks selling milk products to the Armed Forces. In 1918, the business was sold to Anglo-Swiss Nestle.Two years later the factory was outfitted with machinery to process evaporated milk, and three years later the name was changed to Nestle’s Milk Food Co. of Canada Ltd.

The mid 1930s saw the Chesterville facility operating at full capacity, turning out 450,000 cases of condensed, evaporated and baby food annually, work that led to the injection of $700,000 (more than $16 million in 2025), into the pockets of local milk producers. All of this activity meant that near the end of the decade the condensery produced more than 25% of Canadian canned milk, making it Canada’s largest milk cannery and “milk king,” in Dundas County.

Instead of encouraging Canadians to join the United States, the tariffs led to a renewed sense of nationalism, strengthened internal trade, helped diversify the economy, built new international partnerships and saw the imposition of retaliatory tariffs.

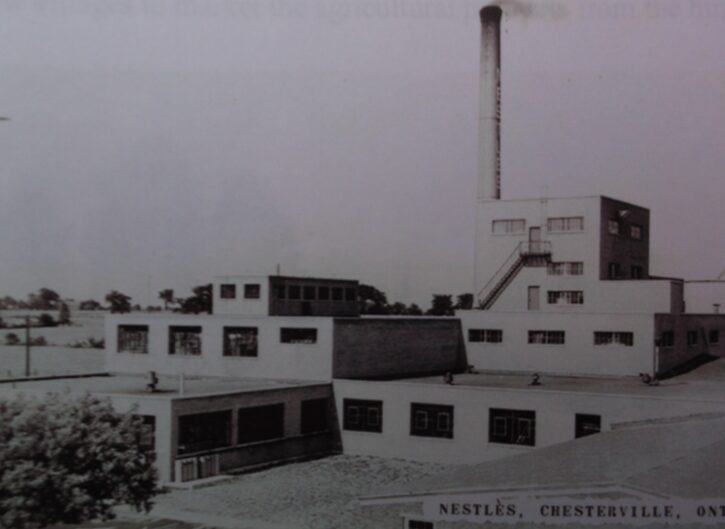

Photo 1) A 1920s era postcard showing Nestle’s Concentrated Milk plant, located on the north side of the railway tracks, directly across from Chesterville’s train station.(Courtesy,The Time That Was a History of Chesterville & District.)

(Photo 2)A postcard of Nestle’s Chesterville Plant,from the 1950s.In 1952, the Plant shipped more than a million cases of condensed milk, employed 120 people and purchased $2 million ($22.3 million today) worth of milk from local dairy farmers.